People around the world rely heavily on fish as a nutritional resource and economic commodity. Fisheries scientists, policymakers and other key players in these food systems gathered in Seattle in early March to discuss the latest research, trends and challenges for the world’s fisheries at the ninth annual World Fisheries Congress.

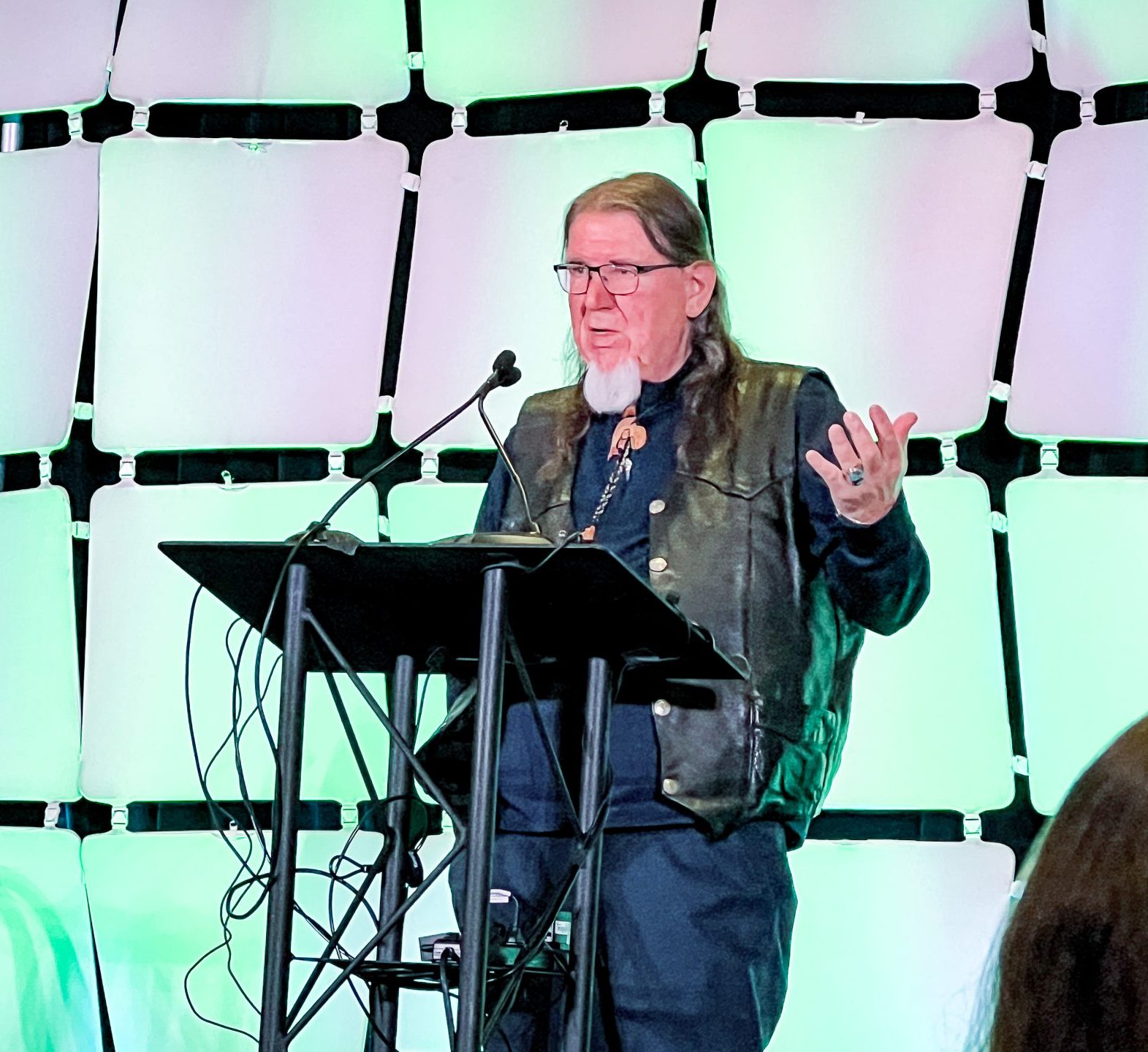

With a roster of 1,600 registrants from 81 counties, the gathering offered a prime stage for NWIFC Chairman Ed Johnstone and Suquamish Chairman Leonard Forsman to provide perspective on fisheries issues from the region’s treaty tribes. Both were plenary speakers at the start of the event.

“Like you, these fish are international travelers,” Forsman said of Pacific salmon integral to the cultures of tribes in the Pacific Northwest. “So we rely on each other for good management.”

Forsman brought with him 16 of the Suquamish Tribe’s culture keepers, who shared songs about the salmon lifecycle and about caring for the waters the fish inhabit. He also reflected on the legacy of Chief Seattle—a signatory to treaties securing tribes’ rights to fish, hunt and gather in the state of Washington, and after whom the event’s host city was named—and about the challenge of maintaining those rights amid local and global environmental change.

“We continue to fight for those rights and to fight for the health of our salmon, shellfish, animals, and all of the marine and land resources we have relied on for our way of life,” Forsman said.

Johnstone noted how human development and climate change are impacting the region’s salmon populations, which rely on a variety of habitats—from mountain streams to river floodplains to open ocean—during their lifecycles.

Despite the ocean’s vastness, Johnstone said, water temperatures, currents, acidity and other factors are changing in response to human activity. The health of smaller-scale rivers and streams is degrading even more rapidly, with a loss of glaciers, shift in precipitation patterns, warming of the water and other changes.

“The tools that we use to manage these fisheries are becoming outdated because of these environmental uncertainties. This is a difficulty we face as fisheries managers,” Johnstone said. “Some years our fish return, sometimes they don’t. Sometimes they’re supposed to be abundant, but it’s a bust. Things are changing so fast that often we are missing the mark.”

Tribes continue working to sustain salmon runs and the fisheries promised to them in perpetuity in treaties with the United States government, and rely on others in government, nonprofit, and private science and policy spheres to fulfill their roles in fisheries management.

“We are so grateful to have so many people with good knowledge working on these issues,” Forsman said to the World Fisheries Congress crowd.

Fisheries scientists from several NWIFC member tribes participated in the multi-day event including from Nisqually, Puyallup, Stillaguamish, Swinomish and Tulalip.

“What does salmon mean to us here in the Pacific Northwest? It means everything,” Johnstone said. “And it comes with great responsibility.”

Above: NWIFC Chairman Ed Johnstone orients as many as 1,600 World Fisheries Congress attendees to where they gathered, in the homelands of Northwest treaty tribes, in Seattle in March. Photo by Tanner Scholten, World Fisheries Congress. Story by Kimberly Cauvel.