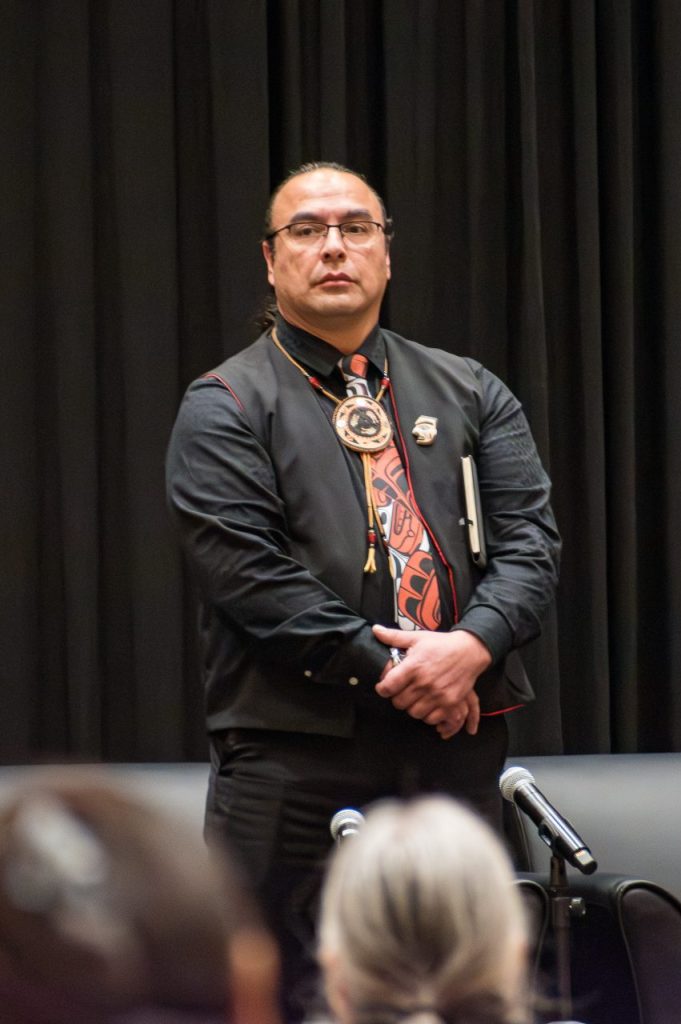

When Muckleshoot Chairman Jaison Elkins welcomed US v. WA 50 attendees to the tribe’s event hall on February 6, 2024, he shared memories from his childhood of elders reassuring him that they had the right to harvest salmon from local rivers.

“We’re not poaching, we’re providing,” he recalled them telling him.

Now with his own children, ages 8 and 2, he wants not only to see the tribe’s fishing culture survive another 50 years, but for opportunities to harvest and eat salmon to grow rather than decline.

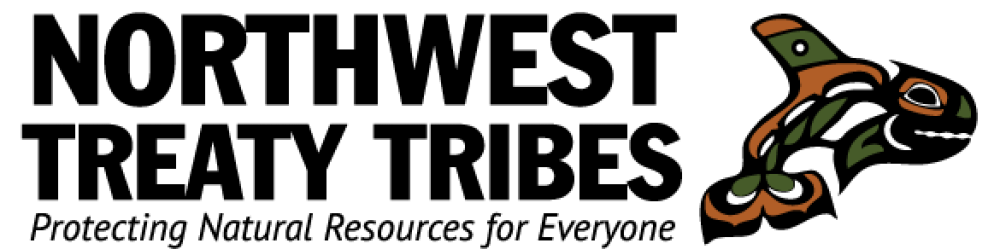

Event emcee Bob Whitener, of the Squaxin Island Tribe, described the importance of teaching today’s younger generations about tribes’ fishing histories, including the Boldt decision, the Fish Wars, the treaty signings and the living-off-the-land lifestyle that came before.

“We have important history,” he said. “It just can’t be in a book; we have to tell our children.”

Above right – NWIFC Chairman Ed Johnstone is blanketed by executive assistant Jennifer Green (left) and his daughter, clerical lead Alice Johnstone. Johnstone accepts a paddle from the Nisqually Indian Tribe and prompts a laugh from Nisqually Chairman Willie Frank III (left) and the crowd during his speech.

Speakers reflected throughout the event on personal memories, ancestral history and the future, with an eye toward embracing Indigenous knowledge and Native resilience to sustain salmon through climate change and other current threats to tribal treaty rights in Washington state.

“As hard as times were, you had to find ways to have some fun,” said Upper Skagit elder Doreen Maloney (center).

Maloney evoked laughter from the audience and was applauded during her rousing retelling of experiences during the Fish Wars and since. She received a standing ovation at the end of her talk.

Across generations, Stillaguamish fisheries director Kadi Bizyayeva (left) and Upper Skagit elder and general manager Doreen Maloney shared their views on the Boldt decision and ongoing challenges for treaty fisheries.

“We need to work together,” Bizyayeva said of tribes and other government agencies.

While co-management with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW) has progressed in that regard since the 1980s, annual fisheries negotiations, tensions between tribal and nontribal fishing groups, and persistent environmental and political threats to fish health remain challenging.

Current and previous WDFW leadership joined tribal leaders on stage to discuss these issues.

Warren King George (above, left) of Muckleshoot said that access to salmon, as well as berries, elk and other resources, remains critical to Coast Salish people for physical and spiritual nourishment.

“Even though our (harvest and cooking) techniques have changed, we use these foods as part of our identity, to remind us who we are and where we came from, and to strengthen ourselves,” he said.

Representatives of Native communities in Oregon and Alaska joined the event, sharing their perspectives on and current work to restore salmon in their home regions.

“We can’t give up … When the tribes get involved, the resources bounce back, with our knowledge, our resources and our culture,” said Mike Williams (center) of the Akiak Native Community within the Yukon River watershed. Williams was joined on stage by Kat Brigham of the Confederated Tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

Fawn Sharp (above, right), vice chair of the Quinault Indian Nation, spoke about tribes’ resilience despite the challenges faced, from the Fish Wars era to modern day climate change.

“In another 50 years we are still going to be here, and we will be even stronger,” she said. “While sometimes it seems like the whole world is on fire, when you look at us as Native people, we are growing stronger, we are growing more resilient.”

Climate change and the state of the environment have created a sense of urgency for tribes in their efforts to maintain access to natural resources. “I feel so much is at stake right now for our next generations,” said Glen Gobin (above, left) of the Tulalip Tribes.

It is more critical than ever that tribes speak up for and act on behalf of the ecosystems that produce their traditional foods and medicines. “As we move forward, we are going to continue being the sentinel and the beacon for the environment,” said Suquamish Tribe Chairman Leonard Forsman (center).

Already, through investments in habitat restoration and hatchery operations, tribes are leaders in preventing the region’s salmon runs from slipping into extinction. “If it wasn’t for the tribes, there wouldn’t be any salmon.” said Lisa Wilson (above, right), NWIFC vice chair and Lummi Indian Business Council member, during a panel discussion about how treaty rights remain at risk because of modern environmental issues.

Above left – Russell Hepfer of the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe (left) invites the tribe’s chairwoman Frances Charles onto the stage during a panel about salmon recovery wins including the removal of hydroelectric dams on the Elwha River.

“We’re not ‘dam(n) Indians’ anymore; we took that damn dam down, and we got our damn fish back,” Hepfer said to cheers and applause from the crowd.

Above right – Scott Schuyler of the Upper Skagit Indian Tribe spoke at US v. WA 50 about the successful growth of Baker River sockeye runs after fish passage was implemented at hydroelectric dams on the river, and about his hope that the next generation of tribal leaders will forge ahead with similar projects on the Skagit River and elsewhere that salmon recovery is needed.

“It’s up to us to speak up for the fish,” Schuyler said. “Our ancestors have guided us so far and now we have to rely on our young people to carry out what’s next, dam removal or anything else.”

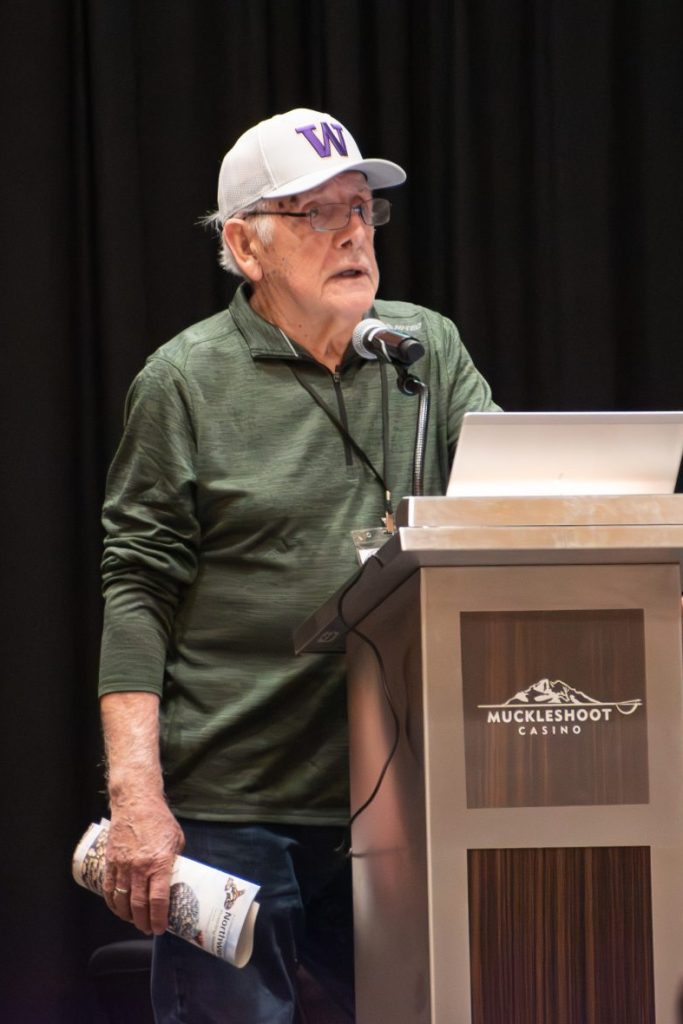

Judge George Boldt’s family was honored throughout the two-day event, in recognition of Boldt’s impact for treaty tribes and the challenges the family endured during the high-stakes case.

Virginia Boldt Riedinger and her son Jeff Riedinger, Judge Boldt’s grandson, were honored with a song from the Muckleshoot Canoe Family.

The Nisqually Indian Tribe also honored Judge Boldt’s descendants with a paddle. When accepting the gift, Virginia Boldt Riedinger described her father’s courage and steadfast belief that the decision he made in U.S. v. Washington was the right one.

“I’m in my 90s, so I remember the 1970s and the grief that everyone went through well,” she said. “Father never wavered in his decision. He believed it would benefit the tribes, the state, the nation—and I’m seeing he was right.”

Many attendees recalled Billy Frank Jr.’s leadership in fighting for treaty fishing rights and environmental protections.

“To see our people out here fishing and enjoying life is what this is all about,” said Billy Frank Jr., as a boat went by his family’s fishing spot on the Nisqually River in a video shown at US v. WA 50.

So long as tribal members had sustenance, they had joy. Frank spent most of his life sharing that truth as far and wide as he could outside Indian country, advocating for treaty fishing rights and environmental stewardship in the Northwest.

Billy’s son Willie Frank III (left), and many who counted Billy as a friend during his lifetime, spoke of his determination and ability to disarm people of all stripes.

Billy’s son Willie Frank III (left), and many who counted Billy as a friend during his lifetime, spoke of his determination and ability to disarm people of all stripes.

Bill Kallappa, of the Makah Tribe, said Billy’s humor was a uniting force, and his ability to speak plainly—like once referring to sewage as “turds” in an important meeting—was admired. His energy brought people together.

“He was a light we could all follow. A brilliant, brilliant light,” Kallappa said.

Willie Frank said he’s proud of how far tribal communities have come since the Fish Wars era. Back then, his father was arrested more than 50 times and tribal culture, from fishing to Native languages, was nearly snuffed out.

“To be alive and Native today is to have survived genocide,” he said.

New generations of Northwest tribes are now growing up with their treaty rights backed by the Boldt decision and myriad proceedings that followed, with tribal history taught in Washington state’s public schools, with tribal flags flying not only on reservations but also in other public spaces, and with Native people filling important roles across all levels of government.

“The current generation is able to learn their culture in a supported way; not like we did, when our cultural practices were suppressed,” said Leonard Forsman, chairman of the Suquamish Tribe.

Four witnesses from different tribes each shared powerful insights with the audience at the close of the event.

“It was unimaginable to my grandparents that anything like this would have happened. They had no idea the success we would have.” — Ron Charles, Port Gamble S’Klallam

“Our very existence is rooted in this place, these lands and these waters. Our effort to restore these resources is imperative.” — Cecilia Gobin, Tulalip Tribes

“Boldt is a true success story in the court system. But it’s fragile.” — Chairman Timothy “T.J.” Greene, Makah Tribe

“Our work is not done. Our fight is not over. Warrior up; it’s time to educate our next generation.” — Jaimie Cruz, Squaxin Island Tribe

Event breaks offered opportunities to connect with tribal culture.

Youth had a creative and engaged presence at the event, with poster projects from a Quil Ceda Tulalip Elementary class on display and a trio of North Thurston High School students sharing their insights from the event.

Below left – North Thurston High School students (left to right) Greta Tuttle, Alice Bennett and Danika Francis took the stage to share their main takeaways from US v. WA 50.

“It was really cool to hear from people who were actually there and remember it, instead of learning everything secondhand,” one of the students said.

Below right – The students, along with some of their peers, also designed a game that taught players about salmon and rewarded them with hand-crafted stickers and buttons about tribal fishing rights.

NWIFC organized the event, with sponsorship support from member tribes Muckleshoot, Tulalip, Nisqually, Squaxin Island, Swinomish, Elwha, Jamestown S’Klallam, Lummi, Port Gamble S’Klallam and Suquamish.

“I’m really proud to be carrying on the work of our elders, to try to protect and push forward our way of life,” said NWIFC Chairman Ed Johnstone (below, right), of the Quinault Indian Nation.

NWIFC executive director Justin Parker and Vice Chair Lisa Wilson (below, left and center) each addressed the crowd at US v. WA 50, then paused for photos together after receiving blankets at the event.

Photo essay by Kimberly Cauvel.