With warming ocean temperatures and more frequent and intense harmful algal blooms occurring, the Makah Tribe wants to better understand how toxins travel through the food chain to marine life and humans.

“We are looking at several types of fish to see if and at what levels domoic acid and saxitoxin exist in their systems and how those levels change throughout the season as algal blooms take place,” said Adrianne Akmajian, the tribe’s marine ecologist. “We are also looking for the toxins in gray whales since they feed in the nearshore and lower on the food web.”

The toxins are known to cause shellfish poisoning in humans when ingested. Domoic acid causes amnesiac shellfish poisoning, and saxitoxin causes paralytic shellfish poisoning.

Akmajian has studied the levels of both toxins in sea lions.

“Domoic acid in particular is well known in California for causing sea lions to have seizures and aggressiveness,” she said. “In other parts of the world, saxitoxin has caused respiratory paralysis in several species of whales and seals.”

Now she wants to target fish and study the potential exposure to human health.

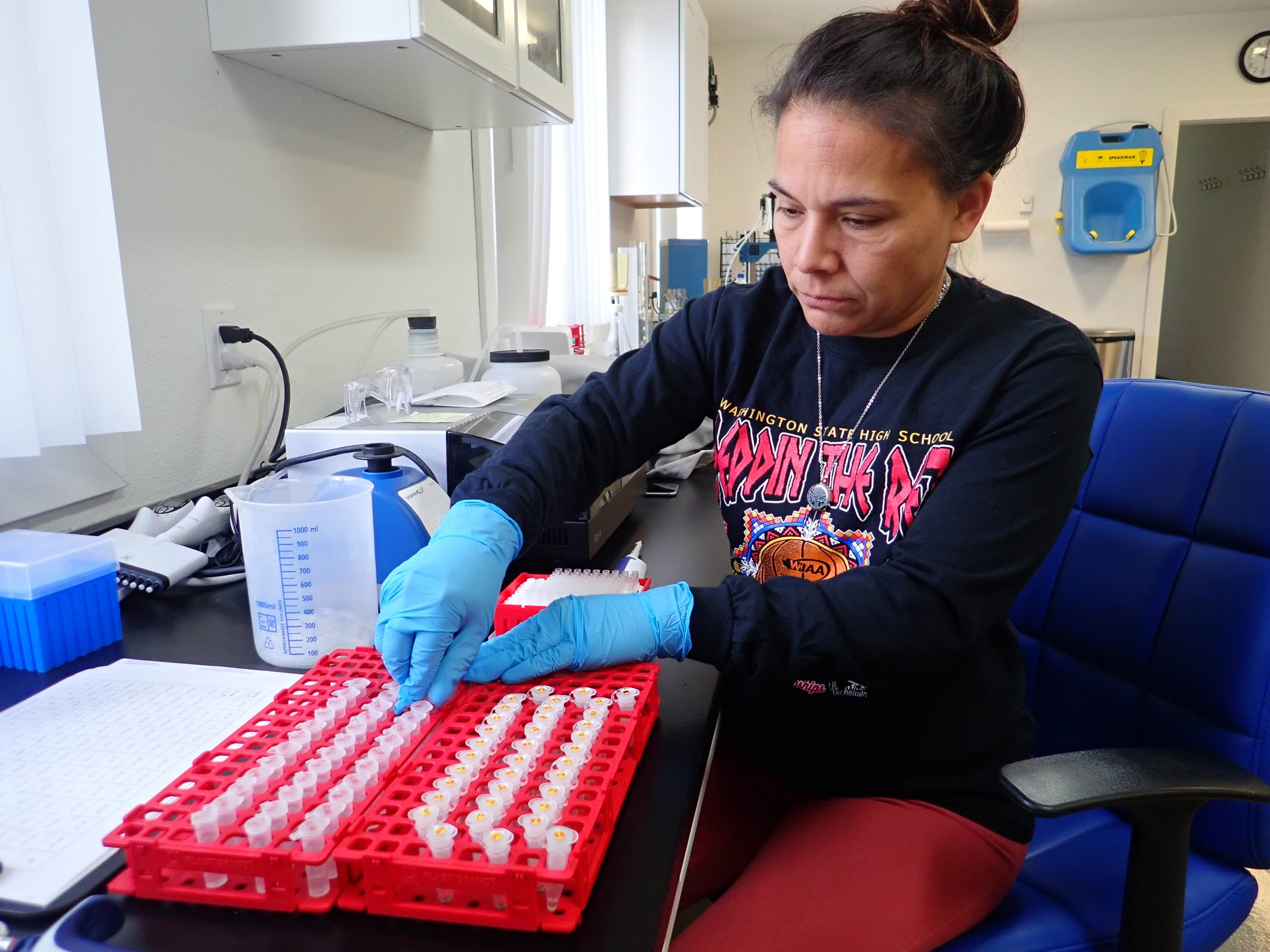

Since 2018, the tribe has been sampling fish caught by several of the tribe’s commercial fishermen, analyzing toxins in fish stomach contents and in fillets.

Fish tested include chinook salmon, yellowtail rockfish, petrale sole, walleye pollock, spiny dogfish, arrowtooth flounder and skate. The tribe samples fish monthly from May to November, with increasing frequency when active algal blooms are detected in routinely monitored shellfish.

Based on other studies, Akmajian says she does not expect the toxins to make their way into the muscle tissue, but if there is a big bloom, they could see higher levels of toxins in the fillet.

“By analyzing for toxins in both fish muscle and internal organs, our results may inform fish catch practices, such as how to quickly clean and gut fish or to quickly place them on ice so the toxins cannot leach out of the stomach and into the fillet tissue that humans consume,” she said.

The tribe also is studying the toxins in gray whales by sampling their scat.

“This is done by following the whales closely in our research boat,” she said. “When we see the water discolor, we rush in and use nets to scoop out the material.”

Gray whales feed in the nearshore and on the sea floor and may be more exposed to the blooms that produce saxitoxin, which typically occur in nearshore bays. In the summer of 2019, shellfish harvest was closed around the Makah Reservation for several months due to high levels of saxitoxin in monitored shellfish.

“We will be interested to see if some of the saxitoxin made its way into the whales as well,” she said.

Lora Halttunen, Makah Tribe marine ecology technician, prepares to transfer diluted toxin samples into tubes to be spun in the centrifuge. Adrianne Akmajian, Makah Tribe